The Eternal Castle [Remastered]

by Leonard Menchiari, Daniele Vicinanzo, Giulio Perrone

Windows/Mac/$10/4 hours

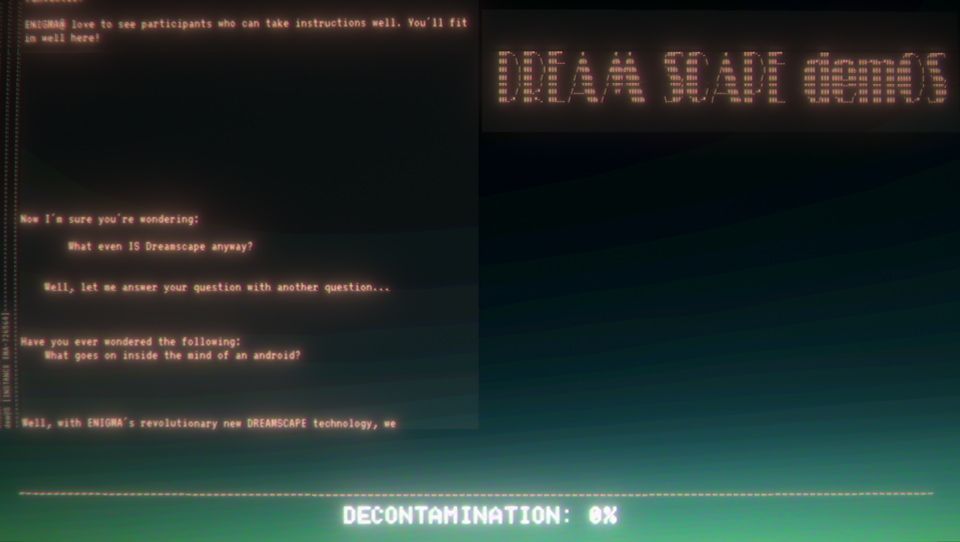

"The Eternal Castle [REMASTERED] is an ambitious attempt to modernize an old classic in order to keep its memory alive. Through detailed research and hard work, the production team tried to expand the experience while keeping the same 'feel' and emotional flow of the original masterpiece from 1987."

I'm taking a bit of a gamble on this one — I saw it on 'Six Second Trailers' this morning and instantly bought and played it. There's a chance it will turn out to be a big commercial hit and people will wonder what it's doing on this blog, where I try to recommend you a game you might not otherwise play. But I enjoyed it enough that I wanted to write about it anyway.

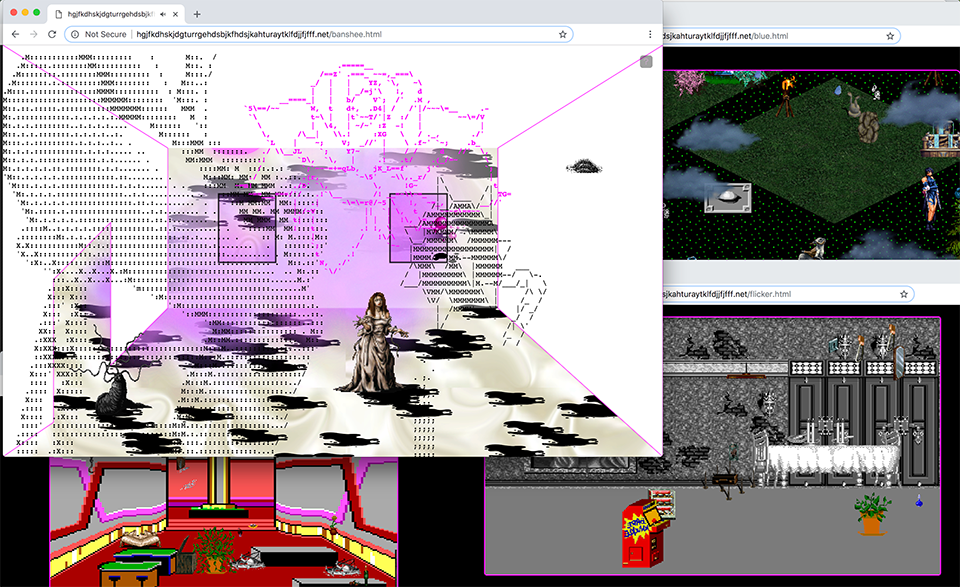

The description quoted above, from The Eternal Castle's store page, can't be taken literally — the game is a passionate love letter to Prince of Persia and Another World, neither of which had been released in 1987. Like those games, Eternal Castle takes a technical, somewhat realistic action-platforming system, and uses it as a canvas for telling a cinematic adventure story. The 'Remastered' conceit, I suppose, is there to frame your expectations, since the game is somewhat more rugged and unfriendly (some might say 'janky') than recent high-budget games in the genre, like Inside.

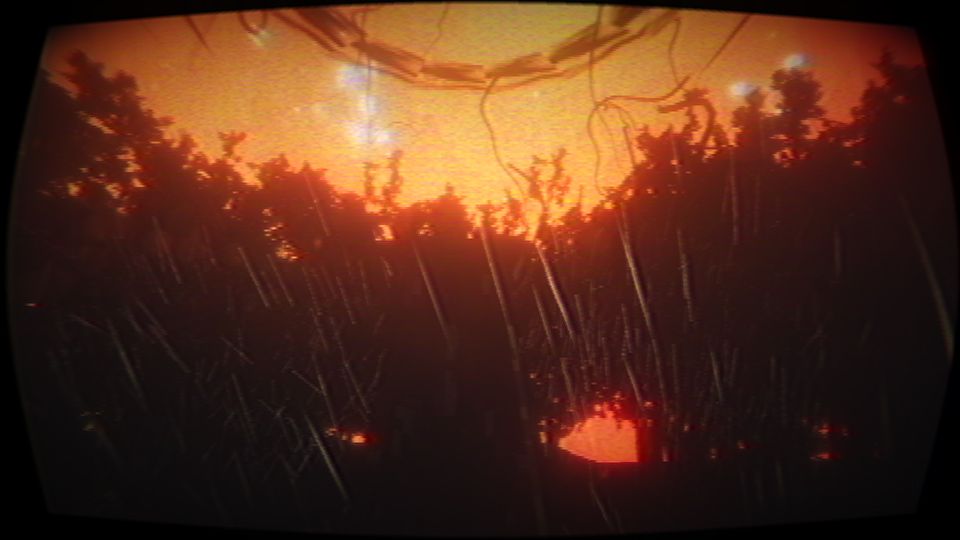

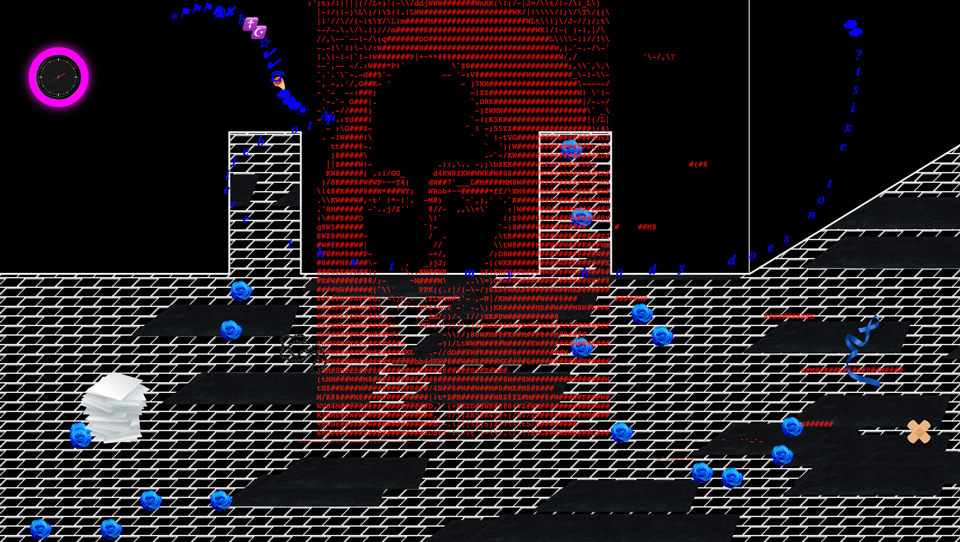

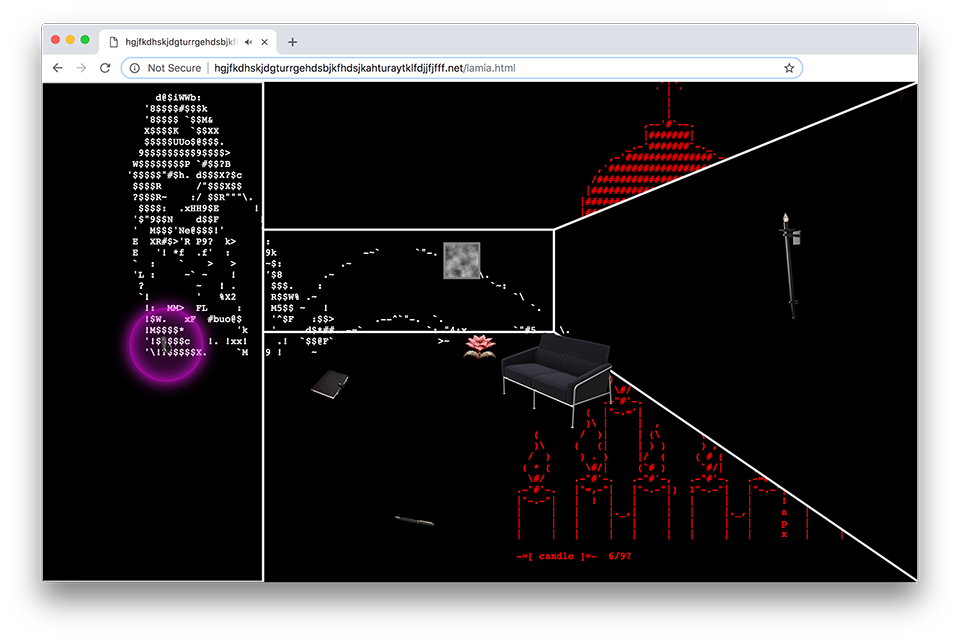

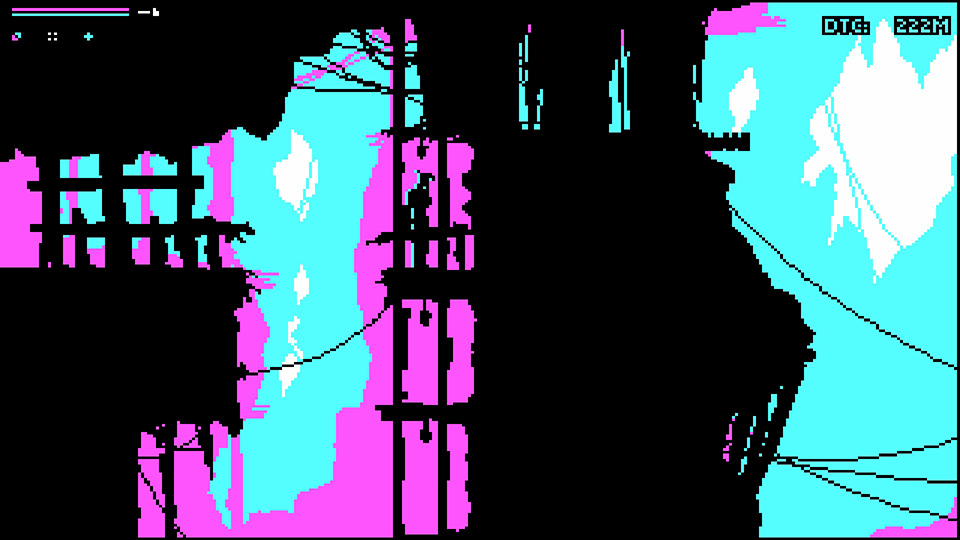

I love how this game looks, from beginning to end. Actual CGA games did not use the four-color palette this way — they tended to try to mitigate the lack of color by using using all four colors on every object, and by using dithering to make the colors blend together. Eternal Castle instead embraces the palette, to create large areas of the screen that are either retina-burningly bright or totally black. This intense contrast creates a sense of light and distance that I don't recall ever seeing in a CGA game.

The action mostly happens in cross-section silhouette, reminiscent of the 1991 Amiga game Blade Warrior, or more recently NightSky or Feist or Limbo. For me it works much better here, partly owing to the ultra-hot palette, and partly to the subtle use of 3D light tricks to fill out the space. It's worth playing Eternal Castle just for how it looks and sounds.

At their best, games in this genre of 2D cinematic action adventures create a sense of place that cannot exist in games where you can explore the space more completely. You can see far into the distance in almost every part of Eternal Castle, but you can only visit a two dimensional slice of its world — just enough to sketch out a much bigger expanse. The game uses camera tricks, dramatic set pieces, sound and special effects to give this dolls-house world a sense of materiality which is quite unusual for 2D games, old or new.

In the same way as the games that inspired it, Eternal Castle tells a story almost entirely without words, and without overtly explaining anything about the world you're exploring or its history. Like the constrained art style, this gives the game room to expand and breathe in your imagination, making it feel richer and cooler than a modern open-world AAA game where you are invited to zoom in on every molecule of the place and its story.

It's hard to take something that is such an unabashed homage to early '90s videogames and write about it in a way that doesn't boil down to "if you liked Another World or Flashback, you'll probably like this". But that framing does a huge disservice to Eternal Castle, as though there were nothing here except nostalgia, when in fact very little of it feels generic or cliché.

Let me put it this way, instead: there is a handful of games that I wish I could forget or make strange, so that I could experience them with the alien wonder that they had on the first play. Eternal Castle is unique enough that it felt like I was playing Another World for the first time.