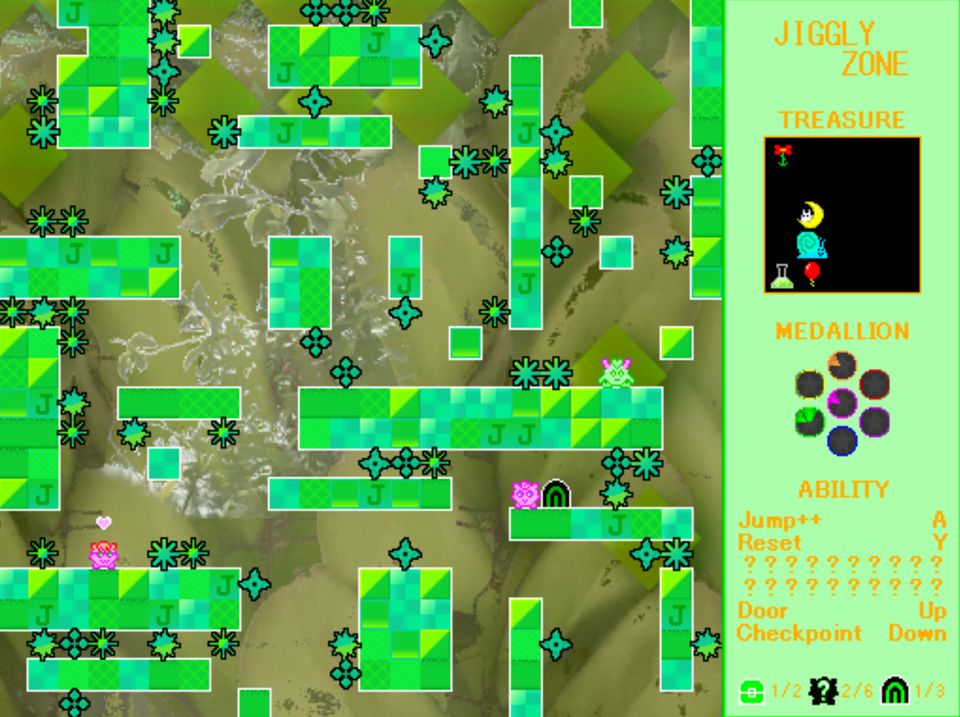

JIGGLY ZONE

by

Sylvie and Hubol

Windows/Free/~3 hours

"Welcome to the JIGGLY ZONE. Become JIGGLER and find the Medallions scattered Throughout the land."

I came to this one through the repeated, insistent recommendation of Blake Andrews, Babycastles veteran and longtime contributor to Glorious Trainwrecks, the online home of trashgames and B-games. I wasn't previously aware of the works of Sylvie and Hubol, but they have been prolific producers of free games for the last ten years, always in a B-game style.

Designers of free games don't organize neatly in genres or movements, so probably it's a bad idea to apply terms like 'B-game' or 'trashgame' or 'kusoge' to other people's work. Maybe the easiest way to explain a game like JIGGLY ZONE is to say that for the last ten years, a small set of game designers has resisted the virulent, near-total commercialization of independent games. When you set out to make a videogame you can sell for money, you implicitly accept a large set of norms and orthodoxies around value and quality — for example, commercial games have to look and sound attractive. All the art and sound in them must be original. A commercial game has to be of a certain length relative to its price. It has to be accessible and easy to understand. Most broadly, commercial videogames are not allowed to be terrible in any one dimension... and this comes at a steep price, which is that they are usually not brilliant in any one dimension, either.

When B-games are ambitious, which they often are, they tend to be ambitious in a way that is laser-focused on one single element. This lightness allows them to pursue that one element, be it a mechanic or a concept or a joke, in a way that is forbidden for commercial work.

Here, then, is the reason why you should play JIGGLY ZONE: unencumbered by the need to do everything, it does one thing — level design — to perfection. I loaded it up with a degree of apprehension: do I really want to play another masocore 2D platform game? And then, in spite of myself, I was seduced by the virtuosity in the placement of the blocks and hazards, and the way they give life and depth to the game's action mechanics.

JIGGLY ZONE has a very simple and familiar structure: you are given a nonlinear 2D world to jump around in, and you must collect a bunch of treasures, most of which are squirreled away in places that are hard to jump to. Some of the treasures grant additional powers of traversal, in that familiar Metroid-inspired way, and the game also provides one generous gift from the outset, which is that you can place a checkpoint by pressing the down arrow whenever you are standing on solid ground. The cadence of play, as a result, is rapid staccato repetition: you line up a jump that looks difficult but feasible, you place a checkpoint, and then you attempt that single jump over and over again until you get it right.

JIGGLY ZONE's world is made up of just two types of objects: deadly blocks and solid blocks, and so the substance of the game is just the particular placement of these blocks in each level. At first glance, the placement seems haphazard and almost random. But as you inch through the world, placing checkpoints and forming hypotheses about which jumps are makeable and which are not, you realize every single block has been placed with great care and ambition. The level design starts simply enough but it progressively guides you through the details of the mechanics with a level of granularity I have never seen before: how high is my third double-jump? How much height do I lose if I jump into the ceiling? By the end of the game, it has become the most technical and original platformer I can remember playing, but it is all in the arrangement of the blocks.

I've talked about invisible forms of beauty before on this blog, when I wrote about the puzzle design in Mirror Drop. JIGGLY ZONE has a great soundtrack, but it is a visually hideous game, with a character borrowed from Pokémon and no appreciable story, no high concept, no sense of place. Still, as I worked my way through the game, finding the hidden loopholes and tricks that made impossible obstacles just-barely-possible, I felt that same sense of awe and joy that I feel looking at masterpiece paintings or listening to favorite records.

Invisible beauty, encoded in the virtuosic placement of two types of pixellated block.